fbar

Former Harvard Chemistry Chair indicted for failing to file FBAR and filing false tax returns

IRS Hard at Work Despite the Pandemic Individuals, who have failed to report their foreign…

Courts Split on FBAR non-willful Penalty

Should FBAR non-willful penalty be charged per form or per account? The Courts have recently…

Quiet Disclosure Guilty Plea

Florida man pleads guilty to tax evasion and hiding funds around the world In April…

Kenyans to Disclose Offshore Income and Assets or Face Stiff Penalties.

Global Tax Initiatives and Kenya. Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) has thrown down the gauntlet, advising…

The Non-willful FBAR Penalty and the Slow Death of Reasonable Cause.

Non Willful FBAR Penalty Ruling. A December 2017 decision of the Court of Federal Claims…

FBAR Collections Ten Billion and Counting

IRS Releases 2016 Offshore Voluntary Compliance Statistics On October 21, 2016 the IRS released the…

Outrunning the IRS: FBAR Statute of Limitations Guidelines

What Happens If Someone Fails to File an FBAR? A wrinkle in the law for…

Finding an FBAR Lawyer to Help Avoid Criminal Charges

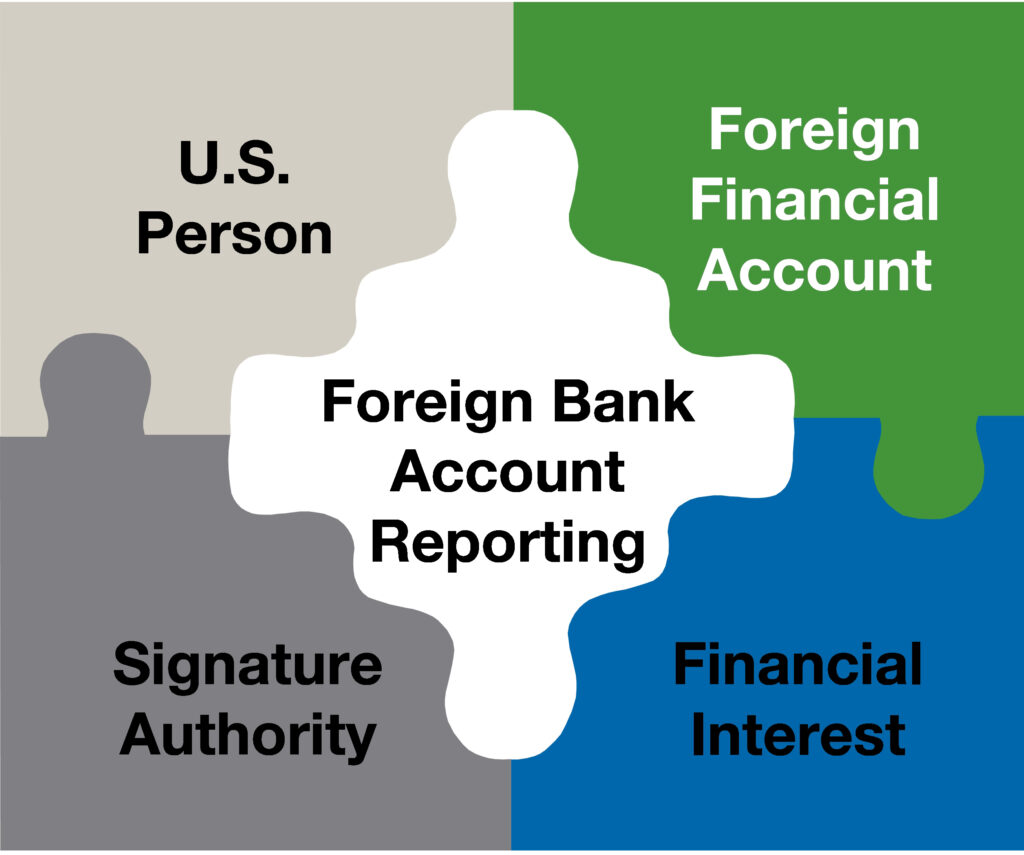

How to Find a Good Tax Attorney You’ve discovered you have to file the Foreign…

No 5th Amendment Privilege in Submission of Foreign Bank Accounts Records

The US District Court for the District of New Jersey has applied the required records…

FBAR Failure Leads Connecticut Executive to Plead Guilty to $8.4 Million Tax Evasion

Prosecutors announced Jan. 20 that a Connecticut business executive has pleaded guilty to willfully failing…

United States vs Simon in Failure to file FBARs

Failure to file FBARs as a Signatory Authority Failure to file FBARs as a Signatory…